Jackie Dunn, September, 2013

Post-election 2013, waiting for our new government to be sworn in and I’m listening to Julia Gillard’s biographer call her subject defiant and fatalistic as she exhorted those in parliament to ‘take their best shot’ at her before a leadership ballot last year. ‘Defiance’ and ‘fatalism’: could there be a better twofold characterisation of the work of Mary Scott? Could there be a more important moment for us to think on the relevance of the feminist project to the lived experiences of Australian women?

Pain has an element of blank

Emily Dickinson

It doesn’t explain everything, it doesn’t explain nothing, it explains some things

Julia Gillard

________________________

Creator of intense dramas and claustrophobic domestic tableaux, Scott is the mistress of the anxious moment. Gender proscriptions and normative prohibitions; problematised erotics and sublimated traumas; the opaque complexity of emotions: these are her subjects, realised in works that describe direct embodied protests.

Scott’s is an expanded autobiographical practice that uses the self not solipsistically, but intuitively so as to reaffirm the centrality of the body – specifically but not exclusively, the female body – to political and social discourses. In her latest investigation, Black Powder, Scott brings a new tone: a note of urgency. Black powder: fuelled by charcoal, highly combustible but frustratingly slow-burning.

At a critical time in Scott’s practice as a mature artist, she is making work with keen relevance for our unstable contemporary world, teetering as it does between ‘mere’ disillusionment and end-of-times crises. Indeed, when we meet as part of the Shotgun project, the most conspicuous book on Scott’s desk is Death of the Liberal Class, Chris Hedges’ excoriating account of the evils of corporatism and the death of liberalism in a world of unfettered capitalism, worsening inequality and environmental ruination.

Mary Scott: Black Powder 2013. Installation shot. Compressed charcoal and pastel on paper and gallery walls

Scott, like many of us, thinks hard on the failures of democracy that so alarm Hedges. More pertinently, she has clearly also taken on his chastisement of the arts for failing in its role to dissent and critique. As an artist, she reveals a deeply felt concern for how to ensure her largely ‘subjective’ practice (her words) might yet tackle the bigger picture.

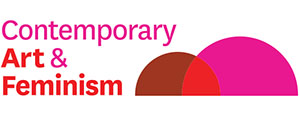

Mary Scott: Black Powder 2013. Charcoal and pastel on paper and gallery walls. 1380 x 1140mm

Of course Scott’s practice is and always has been a political articulation of the human subject in the social domain – if one based on analogy and poetic resonance rather than stridency. As such her images, oscillating between passivity and resistance, act as a corrective to the absence of the body in so many current social and political discourses. Hers is a carefully articulated awareness of the intrusive materiality of bodies, and one of her greatest talents is her ability to remind us that the impact of such crises, discursive or actual, always lands on the body. Scott’s new work continues to insist that powers and desires have their origin in the human body; that bodies are present at the core of a range of experiences and actions, from suffering and awareness to pain and agency. Scott seems to be scoping the different ways in which bodies intrude in times of stress, the way they are lived and produced under duress.

‘How intricately the problem of pain is bound up with the problem of power’, said Elaine Scarry in The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (1985). Scarry – who came to me the moment I viewed these pieces and has not yet retreated – has a lot to offer a reading of Scott’s work: her nuanced and idiosyncratic thesis not only proposes pain as lying at the heart of our humanity, but makes a duality of pain and voice – important to an understanding of Scott’s persistent images of voicelessness.

Pain, says Scarry, destroys language, ‘the power of verbal objectification, a major source of our self-extension’. Body and voice, in their interrelationship, become for Scarry fundamental to understanding the process of destroying (‘unmaking’), and creating (‘making’), the world. Moreover, pain brings about a double experience of agency in which ‘inside and outside ultimately give way to and merge with one another’ and this ‘dissolution of the boundary between inside and outside gives rise to an almost obscene conflation of private and public’.

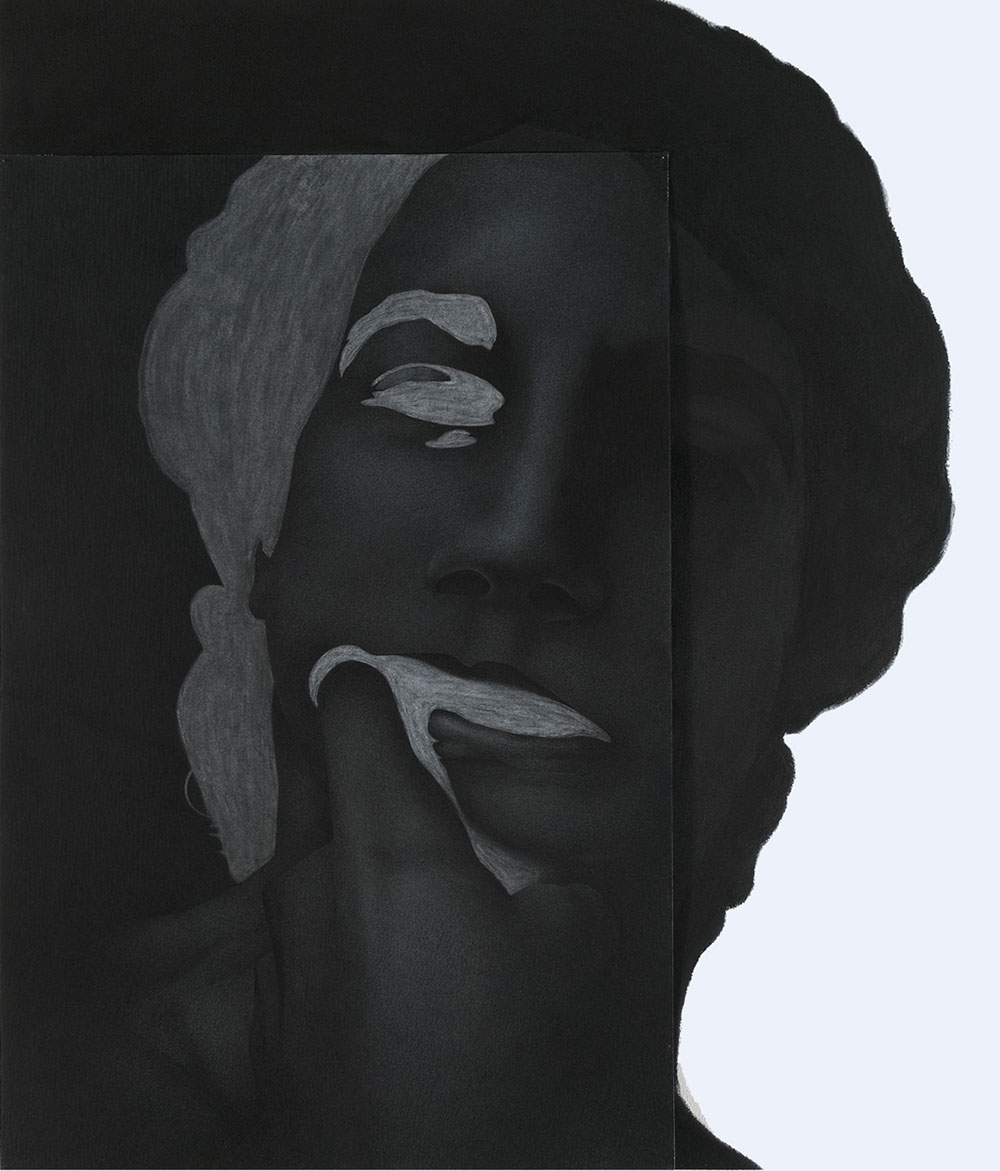

Mary Scott: Black Powder 2013. Charcoal and pastel on paper and gallery walls. 1040 x 1320

Made objects – not just art but all imaginatively-formed ‘artefacts’, abstract or concrete –are projections of those who make them; these have a reciprocal effect, ‘remaking’ those who make them (‘The act of human creating includes both the creating of the object and the object’s recreating of the human being’).

No accident then that Scott points us to brutalism, an architectural movement with a lost originary ideology that was socially progressive, and a failure mired in totalizing regimes of power or, more prosaically, pragmatic corporatism. But I suspect brutalism’s open cipher is what really fascinates Scott here, her interest lying as much in the style’s blankness (incommunicability), as its imposition (will): constrained and constraining buildings, like bodies, silently screaming their muteness.

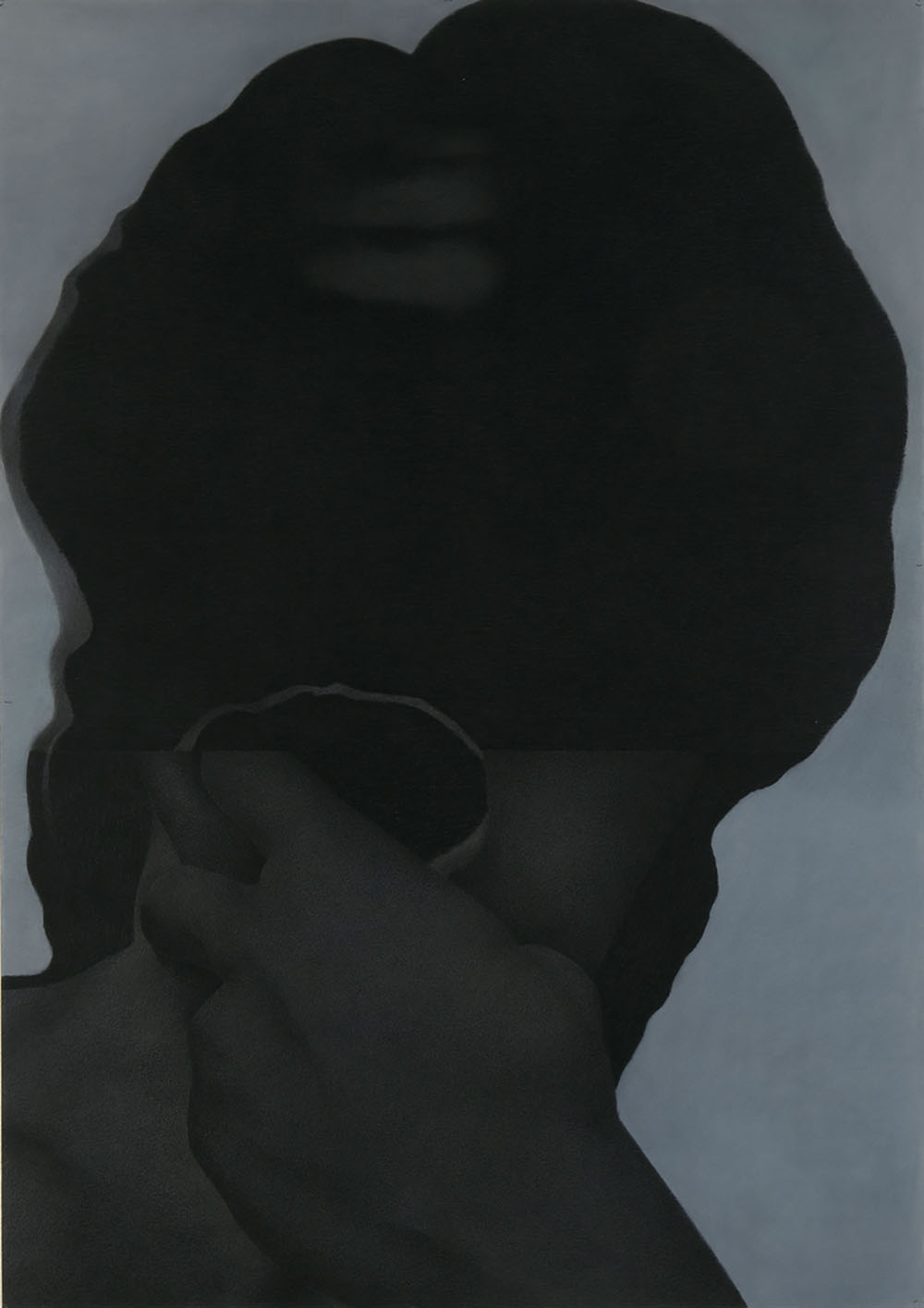

Mary Scott: Black Powder 2013. Charcoal and pastel on paper. 1520 x 1080mm

So, out of shattered language – from Scarry’s ‘inexpressibility’ – Scott creates her personal narrative that will ‘externalize, objectify, and make sharable what is originally an interior and unshareable experience’. But significantly her experience arises in a gendered body. Scott shows us how power converges in and is contested through women’s lived bodies. Her images reveal the bodily impact of systems that encourage and enforce normative behaviours, our negotiation and resistance to them, as well as the role of bodies as tools of political action. She grasps how socially transformative the concept of the phenomenological lived body is: an open-ended, ongoing interaction between subject and world, where each term continuously constructs the other.

________________________

As I tune in to see a new federal cabinet sworn in – one woman in a sea of eighteen near-dead white men – I wonder if Scott has succeeded in holding up to us no less than our exhausted body politic. Manipulated, momentarily silenced by force but resistant and resilient; clinging to utopian ideologies but resigned, in part, to their totalising effect? Have we arrived at an inevitable blankness after the brutal power struggles that enforced muteness painfully, and at great cost? Or is our body politic as tense with resistance as it is with compliance? Maybe between defiance and fatalism lies the slow burning but still incendiary force of black powder.

Reference:

Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Text copyright Jackie Dunn, 2013

Images copyright Mary Scott, 2013

________________________

This essay was previously published in the 2013 Shotgun catalogue. Shotgun is an annual partnership project between Contemporary Art Tasmania and Detached Cultural Organisation, Hobart. Photo credit: Peter Angus Robinson.