EMOTION, RITUAL AND POWER IN EUROPE: 1200 TO THE PRESENT.

ARC CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR THE HISTORY OF EMOTIONS: EUROPE, 1200-1800, at UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE, 11-12 FEBRUARY 2014

“Textiles are produced by situated and active social beings. As products of our material culture, textiles reflect cultural identity, social values, group organization, social status, gender relations, and artistic creativity”[1]

This paper stems from my interest in dowry linen, both for familial connections and for its significance to my current visual arts practice. It is informed by the traditions of dowry linen and needlework in an examination of household rituals. This paper is also motivated by the desire to examine the implications – particularly the emotional implications – behind a ritual, how it relates to its European origins and what it means when these objects are transformed by the passage of time, place and context, as in my case. Furthermore, this paper will address the implications in transforming an essentially private custom/tradition into the public domain via artist interpretation.

It is not my intention with this paper to give a detailed history or social analysis on the multifarious practices and rituals involving dowry. In applying and melding elements of social history, trauma studies and autobiography, my objective is to contextualise this research within the framework of my own creative practice. In doing so, my intention is to gain an insight into the societal expectations, practices and meanings ascribed to dowry linen in central Europe circa 1930s, when my mother was a young woman. With this information, my intent is to then establish the emotional significance this collection of textiles had for my mother, particularly within the context of diasporic homemaking, and how this connects with me familially and translates artistically.

This investigation into the ability of familial objects to carry emotional resonances is motivated by the personal experience of being a first generation Australian raised by Jewish Hungarian parents. In making the decision to leave their European homeland as Holocaust survivors and compelled to choose between significant items to take with them, my mother’s dowry linen accompanied my family on their migration to Australia. This raises questions for me regarding the role these objects played in my mother’s new life: did they enact a symbolic attachment to her homeland? Did they affirm her identity within her new surroundings? And as a first generation Australian how did this affect my perception of my parents’ ability to cope in a foreign environment?

My mother died twenty-seven years ago and I now possess a sizable quantity of her dowry linen and several other objects. The questions I have posed and any research in relation to this linen will be contingent upon several gaps in knowledge. With the passing of more than a quarter of a century as well as lost opportunities to glean anecdotal background information, some historical and personal knowledge will inevitably remain unknown, either through death, neglect or the inability to articulate traumatic memories. Victims of significant cultural trauma such as, in my family’s case, the Holocaust may be silenced by their traumatic history and experiences as detailed in much of the research and the many publications in the field by prominent theorists and psychologists such as Cathy Caruth[2], Marianne Hirsch[3], Brett Ashley Kaplan[4] and Anne Whitehead[5] to name but a few. The resultant postmemory (or second generational) experience could be regarded as another familial ritual whereby sublimated emotions exert tenuous power relations within the family unit[6]. These silences may extend to even the most basic information regarding stories on how family life was conducted, how belongings were acquired and many other aspects of domestic life and the home.

What often remains is the memory of those stories we do know about and the material evidence that is left behind. This material evidence may often “speak” to us in the absence of a primary source. It may take the form of family photographs, letters, family recipes, clothes and textiles. I have chosen to focus on my mother’s dowry linen as it was an integral part of our family life and informed my earliest childhood memories. What these memories and silences reveal in themselves may yield interesting information. I have used this information to inform my art practice employing an embodied, materially challenging visual response to elicit new meanings.

Thus, I will begin with a brief outline on the history of dowry linen in European society with the aim of contextualising my mother’s own textile endowment, then address and contrast female cultural traditions contemporaneous to those of my mother’s, the diasporic homemaking practices of my childhood home, and detail my artistic response to the often problematic combination of ritual, family and identity.

History and context

The creation of textiles, including those intended for dowry, has been practised over several centuries, covering all social classes worldwide. Author and academic Susan Frye notes in her book Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England that traditionally, women communicated stories through weaving or embroidering cloth and that from medieval to eighteenth century England, thousands of women created designs and narratives in cloth. She asserts that women’s embroidered work, and to a less obvious extent “the knots and patterns of sewing, weaving, and knitting” placed these women’s lives within the narratives of “fertility and continuity”[7].

Women’s production of needlework was clearly encouraged by the patriarchy as a means of excerpting order and control over women. Frye quotes Spanish humanist and philosopher Juan Luis Vives from The Instruction of a Christian Woman (1529). Here Vives declares the practice of needlework appropriate for all classes of women because, as he supposed it to be carried out in safe domestic confines, it conformed to his fantasy where this “appropriate activity of women” equated to domestic security[8]. Indeed, through the centuries the value and perception attached to the production of women’s needlework extended to it ensuring the health and wellbeing of household members and the contribution to the household ‘store’. The household store, in turn, demonstrated social rank and household sufficiency.[9] In many European societies, the production of dowry linen often fell to girls and young woman who for years would toil diligently to accumulate this household ‘store’ of items for their trousseau which would, upon marriage, furnish a future home.

The concept of dowry linen as a social indicator is demonstrated in the modern day study of twentieth century rural Greek women by Effstratia Antoniou Katahan in her thesis Stories of an immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles[10]. Katahan details the cultural rituals involving dowry linen where from childhood, women produced textiles in preparation for family life. The ritual of gift exchange also involved the bride-to-be preparing textiles as gifts for the groom’s family, and the groom’s mother in turn providing her son with textiles for the bride’s family[11]. Katahan makes reference to a 1991 study of the women of Kutch, India who spent the majority of their spare time embroidering dowry textiles for their daughters. Young girls actively participated in this culture from an early age producing, accumulating and distributing dowry to female relatives. In her Kutch study, Katahan quotes V. Elson who suggests that these practices “give proof to the girl of her value to her family and establishes the wherewithal for the girl to live up to the expectations she has for her future as a married woman.[12]”

Katahan likens the values from this Kutch study to those in rural Greece. She states that the size and quality of a Greek woman’s dowry traditionally displayed “the bride’s worth and was a vehicle through which the reputation and the prestige of the bride’s family was displayed”[13]. Katahan expands on this in her thesis and links the quality of, and dedication to, the production of dowry linen not only to a woman’s standing amid her community and amongst other Greek women (64, 88, 93) but to the calibre of suitor she could potentially attract (12, 57, 93-95)[14].

Perhaps one of the less commonly observed aspects of needlework and dowry preparation throughout the years is that rather than oppressing women’s identities, in many instances this work helped to forge them. As Frye observes, embroidery as a form of women’s textualities was deployed by women from 1540-1700 to express themselves and in turn redefine the feminine[15]. These textualities offered a view of the creators’ identities within the context of intellectual, familial, religious and historical traditions; even as they redefined themselves via those traditions[16]. Indeed, as Jane Schneider & Annette Weiner observe in their book Cloth and Human Experience, the extraordinary range and inherent possibilities of cloth give “an almost limitless potential for communication”[17].

Frye proposes that through verbal and visual texts and objects, early modern woman asserted and explored her identity. She defines her use of the term ‘identity’ as the “ever-becoming sense of stable ‘self’ that individual subjects attempted to generate through their relations to space, time and discourse.” Frye notes that through this expression, even in the most modest or domestic everyday action, identity is aligned with agency[18].

In the references and case studies referred to above the production of dowry linen was performed by either the family of the intended recipient, by the recipient or a combination of both. The following section of this paper will look specifically at my mother’s dowry linen – an example of linen created independently from the family network. I intend to establish whether the dynamics of identity, intimacy and agency equally apply to commissioned dowry linen, or whether they change accordingly.

My mother’s dowry linen

“Studying the material object offers ways in which to perceive connections between ourselves and the people of the past, as well as to access the contexts that produced the object, contexts that the object continues to recall[19]”

I have very little information on the background of my own family’s dowry linen – including its production, the value placed upon it by my mother, her mother and her grandmother or other household members. Where other writers detail cultural processes and rituals through personal accounts and documented evidence, I am primarily working with large gaps in knowledge and background history. I do know that my mother and her sisters all received dowry linen and that it was not produced by any family member or household staff. I have anecdotal information from my step-mother which would indicate that the procurement and production of dowry linen would be arranged upon a young girl reaching the age of approximately 14 years by her mother[20]. The women of the family (mothers and perhaps aunts and grandmothers) would discuss details such as projected household needs, quantities, fabrics, colours, and styles and sizes of monograms and initials. The work would then be consigned to an outside source to complete.

While my step-mother’s linen is entirely of pink cotton – ordered from Switzerland – my mother’s is mostly cream, with a few pale yellow pieces[21]. I do not know where the fabric was purchased or any other details. The distinctive monograms on my mother’s dowry linen represent the clearest and most personal indication of her ownership of these objects, and her inherent identity. These monograms, all featuring my mother’s family name, suggest a naming ritual linking her family of origin to her future married life. This coheres with what Susan Frye refers to as the memorialisation of a transition in life. In the 1557 painting Alice Barnham and her Sons Martin and Steven, Frye refers to a first-person text in the painting where the subject’s changed status to wife and mother is denoted. Frye suggests that the painting is directed to the subject’s own family in the desire to memorialise the transition and preserve and recall her former state[22]. I would suggest that a woman’s dowry linen could be seen to perform the same function.

While the monograms which adorn my mother’s dowry linen are unusual in their breadth of style, they nonetheless conform to the ideals prescribed by nineteenth century French writer Maurice Mauris. Mauris links the interlacing of letters in monograms to the progress made in script-writing during the 18th century. He recommends the graceful curving form of such ciphers to women as being more “suitable” than the angular (masculine) form of the printed letters of monograms. He goes on to describe in detail the “correct” composition of a “real” monogram, including a treatise on the laws of symmetry. Mauris also recommends the adaptation of the monogram to the object on which it is to appear, and secondly, the importance of appealing to the character and sex of the person whose name it represents[23].

My mother, born Eva Weiss, was the youngest of four children in an upper-middleclass Hungarian Jewish family. Her monogram “WE” (Weiss Eva) adorns almost every piece of her dowry linen in the form of either separate or intertwined initials, decorated or undecorated, in open work or other more standard forms of embroidery. My family research unexpectedly located several variations in the spelling of her family name, including Weis and Weisz. I have adopted the spelling ‘Weiss’ – as it appears on my birth certificate – for my creative work and for this paper.

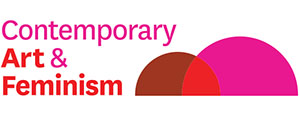

Sylvia Griffin: Dowry Linen monograms for Eva Weiss, sketchbook drawings, 2013

I am intrigued and simultaneously frustrated by the gaps of knowledge within my own family experience. While Katahan identifies similar gaps despite her mother’s oral narrative, I wonder whether such gaps in personal histories could also be applied in cases of familial trauma and dislocation (as outlined in the introduction)[24]. I regard my mother’s dowry linen primarily as the material evidence of her European life and as a link to family members I never knew. For the purposes of my work, I have used artistic license in considering this linen as testimonial objects in the same vein that theorist Marianne Hirsch describes charred photographic images. Hirsch considers that these photographs hold “testimonial and social value” and thus become “documents of everyday life, bearing witness to acts of embodied communal exchange…they can hint at the qualities of familial and communal lives…[25]”.

I am concurrently mindful of the pitfalls in making assumptions based on my own emotional attachment to my mother’s dowry linen. I am aware of the possibility that my mother may not have shared the values I have attached to them. This was made clear to me in my conversations with my step-mother (see footnote19) where my expectations of her attachment to her own dowry linen were not borne out. The overlay of a traumatic past, particularly one such as my step-mother endured involving large-scale loss of family, displacement and migration, manifests in unforeseen ways. For example, I expected her to be attached to her dowry linen as a precious link to her mother and former family life. When questioned, my step-mother claimed to place no value on it at all; in fact she never used it in her transnational homes – instead keeping it neatly folded away in a cupboard[26]. By contrast, my mother used all her dowry linen. I can attest to this as I have strong and emotionally resonant memories of the household rituals enacted between the three generations of women in my childhood home based around this linen.

The gaps in my family history and object knowledge, such as the variations in spelling of my mother’s maiden name, present potentially rich artistic challenges. They offer an opportunity to express absence, mortality and longing – as well as the temporal peculiarities of memory – by attempting to find answers through creative practice which can question and challenge. Additionally, I venture to propose that the performative aspects of an artistic practice bear a sympathetic counterpoint to the embodied rituals in the making and household use of dowry linen. Sociologist and academic Paul Connerton in discussing memory writes of conveying and sustaining recollected knowledge and images from the past by “(more or less ritual) performances”[27]. He continues, arguing that commemorative ceremonies “prove to be commemorative only in so far as they are performative; performativity cannot be thought without a concept of habit; and habit cannot be thought without a notion of bodily automatisms”[28]. Creatively, within this context the line between ritual and habit can blur: a physical act repeated with intent can feel more closely aligned to ritual rather than mere habit.

Marianne Hirsch also refers to Connerton in How Societies Remember in which Connerton describes these rituals or habits as “a knowledge and a remembering in the hands and in the body, and in the cultivation of habit it is in our body which “understands’”[29]. Indeed, the embodied attachment one may feel for objects is multi-faceted. Katahan describes the bond some rural Greek women had with the dowry textiles they produced citing the case of one woman who felt that her professionally embroidered wedding chemise was not really ‘hers’[30]. She kept it wrapped separately to avoid it touching the chemises she had embroidered herself when she packed them together in a trunk[31]. While my mother may not have invested time and labour in the production of her dowry linen, I have little doubt that she formed a significant attachment to its agency to family, home and memory.

Material objects with close connections to the past or to former homes also possess potential to be emotional triggers. Hirsch refers to objects as triggers and our tendency to endow them with our own projections. She quotes Aleida Assman who writes of the ‘return journey’ or the reunification with something left behind as having the effect of a reconnection of severed parts (as in the classical Greek legal concept of the symbolon)[32]. If this happens, the object may “release latent, repressed, or dissociated memories – memories that, metaphorically speaking, remained behind, concealed within the object. Objects and places, therefore, Assmann argues, can function as triggers of remembrance that connect us, bodily and thus also emotionally, with the object world we inhabit.” Hirsch continues, considering the ‘sparks of connection’ and intense bodily reaction to journeys of return[33].

From dowry to homemaking

The emotional links of dowry linen to family, home and tradition would have been particularly relevant on my mother’s emigration to a foreign country. The significance of choosing to include her dowry linen, and the sheer volume of it amidst the allowable luggage in leaving her homeland, indicates the personal value my mother ascribed to these items. I also believe that this linen would have been a means of naturalising a new and at times bewildering environment by bringing the familiar from her “old” world into the new. Referring to the significance of diasporic objects as emotional signifiers in Italian migration, academic Dr Ilaria Vanni uses the terms ‘home’ and its opposite ‘unhomely’ to denote the emplacement and enactment of multiple geographies. She uses ‘unhomely’ as a translation from the Italian ‘spaesati’ which, while literally translating as ‘without a village’ or ‘without a country’, also alludes to the loss of familiar things and surroundings, “being or feeling lost, having lost one’s bearings, being displaced, being confused, being out of place”.[34]

Vanni’s reflections on the Italian diaspora and the importance of personal objects can be applied to the broader migrant experience and the relevance of objects such as dowry linen. Relevant too are Vanni’s references to anthropologist and historian Ernesto De Martino who theorised that the loss of familiar “things, practices, words, habits” etc led to a loss of the “common lifeworld”[35]. The symbolic attachments to this ‘common lifeworld’ after leaving a homeland can be materialised through the diasporic practices of homemaking. This concept is examined by geographers Alison Blunt & Robyn Dowling in their book Home which looks at the complexities of physical, emotional and imaginary attachments as well as concepts around belonging and alienation[36]. Blunt & Dowling see homemaking practices as a means to manifest material and imagined transnational geographies of home on a domestic scale. They propose that the transnational home can be viewed as “performative spaces within which both personal and inherited connections to other remembered or imagined homes are embodied, enacted and reworked”[37].

As an example of this need to feel “at home” Blunt & Dowling refer to Moroccan women bringing those objects which represented “home” to them into their “other home” in Italy. Through these objects or commodities, it is noted, the women affirm their Muslim and Moroccan identities contextually alongside those which display what they have become[38].

For the second generation, these transcultural objects can provide a link to another more mysterious home. As Katahan comments, her mother’s dowry linen became the means by which she was transported to another time and place which she [Katahan] would otherwise be denied the opportunity to know or experience directly. She remarks on the ability of the textiles, when considered alongside her mother’s stories, to assist her in experiencing her mother as a youth and young adult[39]. While I did not have the opportunity to experience such stories, the linen represents a haptic link to early family life resonant with feelings of security and warmth. I have many early childhood memories of drifting to sleep with the raised stitching from a monogram under the skin of my fingers.

Hand in Hand

Katahan acknowledges that, similarly to me, being a first generation child of European parentage, the physical distance between the old country and new can be used as an analogy by which to measure the cultural differences between herself and her mother. She comments on the difficulty of being a product of two cultural worlds and considers that her understanding of her mother’s dowry linen has served as a cultural bridge between these worlds[40].

As a practicing artist, I am particularly aware of the ability of art to offer a means of consolation and resolution. To this end, I have regarded my mother’s dowry linen as a cultural bridge to the past. I am also mindful of the temporal aspects and difficult emotions associated with these two cultural worlds. Just as my step-mother kept her dowry linen close to her but packed away untouched, so did my mother’s dowry linen remain with me, untouched for twenty-five years. The research which led me into the discourse on postmemory trauma redirected my focus to my family history and consequently, to address my feelings of loss through a re-examination of the familial material in my possession.

The familiarity of, and memories triggered by, these dowry textiles carried parallels to what Hirsch has identified as an object’s capacity to affect a ‘souvenir’ relationship to the past. Hirsch writes: “souvenirs authenticate the past; they trigger memories and connect them indexically to a particular place and time. They can also help to recall shared experiences …[41]”. The semiotic concept of the index provided the ideal philosophical framework from which to consider these materials[42]. Accordingly, my mother’s linen could be seen as the material proof of her former existence as witnessed in her monogram and in the stains remaining from years of usage and storage and even in the crease marks where they had been ironed and folded.

Elsewhere, Hirsch refers to a passage in Jewish author Lily Brett’s book Too Many Men where the semi-autobiographical daughter character brings her grandmother’s tea service back to her home in New York promising to reconnect “some of the disparate parts of her life, to find continuity with a severed past – not to bring it into the present[43].” In a similar vein, my predominant response to my family’s dowry linen, photographs and other objects was the need to honour and protect precious memories and connect to my mother’s European past. As a contemporary artist, I am motivated by the desire to express often difficult and emotive themes in a non-didactic, non-representational manner. This particularly applies to much of my current work with underlying references to my family’s Holocaust experience. Highly mediated, representational art, as art theorist Janet Wolff has cautioned, performs the ‘making sense’ for the viewer in lieu of actively engaging them[44]. Like many artists, I see my role as one to provoke, challenge and thereby engage the viewer.

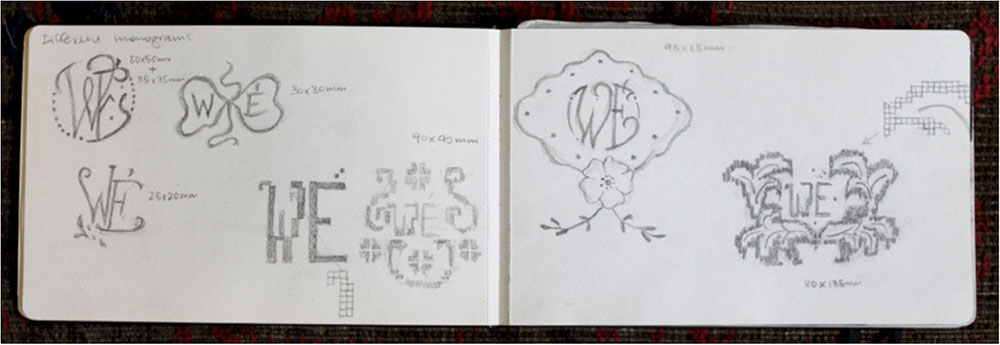

The first artwork I created utilising my family linen was Keepsakes (2012). This installation consisted of six pairs of wax blocks placed on six timber shelves, each lit from behind. Wax was utilised for its resonances of degradability and references to sealing and preserving. The specific dowry textiles used in Keepsakes included two monograms – one from a pillowcase and one from a damask napkin; a fabric button band, and a lacy doily. The monograms were set into the wax and carved to leave a thin wax membrane to enable illumination of the text. The button band – a fabric strip used to secure the openings of pillowcases or doona covers – was loosely tied in a knot to resemble an umbilical cord. Lastly, the doily was utilised twice – once within a wax block, then pressed into the surface of another block leaving a raised imprint. This imprint acted as an indexical void recalling the absent object. The installation imparted an elegiac quality, as I desired.

Sylvia Griffin: Keepsakes (details), 2011

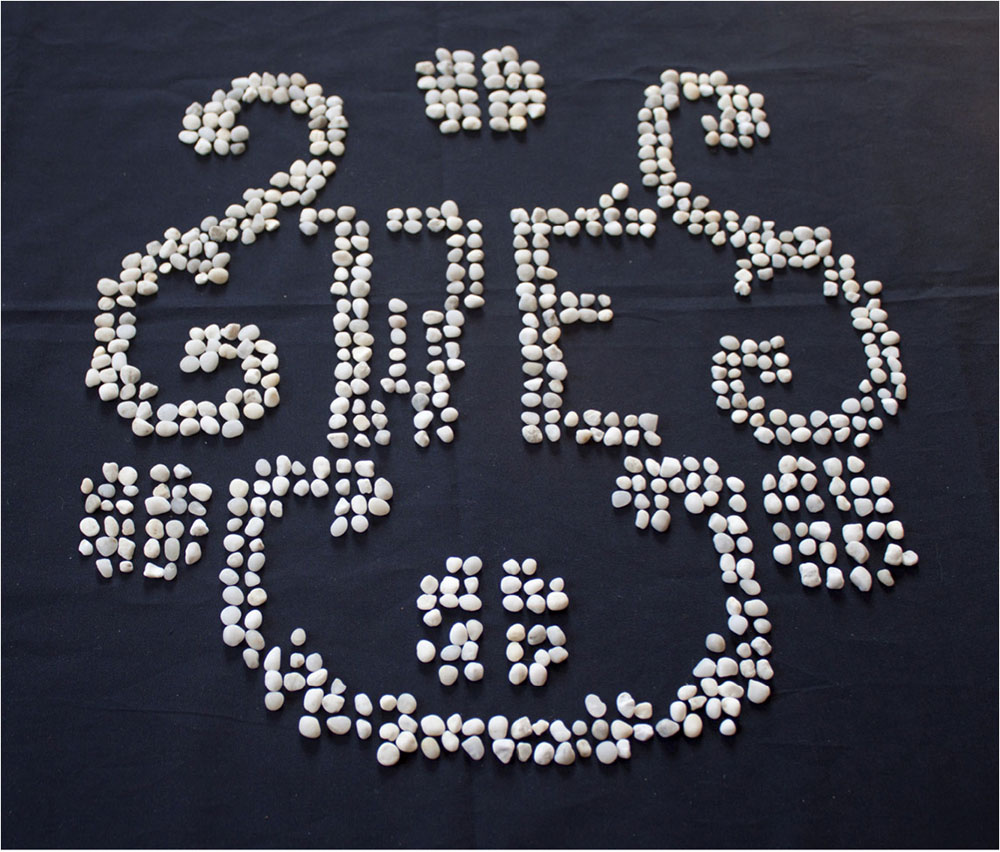

From 2013 my work focused increasingly on written forms of inscription and the relevance of names in memorialisation. This entailed further investigation into my mother’s monograms and thus, dowry linen. In my desire to contribute a new voice in working with dowry textiles I was keen to explore the potential of utilising less predictable material options and chose stone. This appealed for several reasons: it’s hard wearing and long lasting; it has a traditional use in memorialisation, and most importantly for me is its association with the Jewish tradition of leaving a stone or pebble on a person’s grave. This ritual of paying respect to the dead and marking a visitor’s presence seemed particularly relevant to my ambitions. This act simultaneously engages in a ritual which provides a physical means of expressing our emotions as well as our spiritual needs.

Traditional methods such as chiseling and engraving various forms of stone were trialled then discarded after experimentation in favour of individual stones and pebbles. Having collected a supply of quartz stones from the beach over a lengthy period of time, I transcribed my mother’s monogram from a pillowcase to a piece of black fabric. With this stone rendition, which would become the forerunner to my latest work Hand in Hand, the monogram became almost exactly four times the size of the original textile. Despite this change in scale and materiality, the work retained a connection to the original. I developed this piece further by producing a stop-motion video capturing the natural light from a window of my studio raking across the surface of the work. The resultant video suggests temporality in both the material impermanence of the work as well as in the passing of time.

Sylvia Griffin: Monogram in stone, 2013

The rationale behind the piece Hand in Hand was to create a major work for the Graduate School Conference ”Critical Thinking: Research + Art + Culture” 11-27 September 2013 at Sydney College of the Arts, Sydney University. The conference theme within which this artwork was situated was “Space, Place and Country”. In referencing one part of my mother’s dowry, I sought to pay homage to my parents, their former world and the dislocation they experienced. While “Space, Place and Country” provided an opportunity for some contributors to address indigenous or environmental concerns, it provided me with the opportunity to explore what it meant for my family to feel the need to leave their homeland and settle in an environment foreign to them in every way. I was keen to examine the concept of transnational homemaking, the role that familiar objects play in acclimatising to a new environment, and what happens when a ritual within the home is transported to foreign environs.

The inspiration for my contributing work was a small pillowcase measuring approximately 50 x 62cms. The cotton fabric, originally pale yellow in colour, bears my mother’s maiden name initials – WE for Weiss Eva (or Eva Weiss) – in open work embroidery. The decorative edges have been designed to overlap and extend past the actual pillowcase envelope, affecting a lace-like border.

Original pillowcase from Eva Weiss

Hand in Hand, which when translated to stone would become approximately 200 x 248cms, was installed in situ over several days onto a 195 x 250 cm timber support, 7 cm from the ground. The support was draped with an off-white damask tablecloth from my mother’s dowry over the top of one of my own bed sheets. These layers carried the vestiges of everyday use such as coffee, wax and blood stains. I embraced these indexical markers of domestic life, indeed considered them an integral part of the work. The process of translating the embroidered pattern onto a stencilled chalk outline required a careful “reading” of the textile. Thus, the entire installation period was spent with folded pillowcase in hand, counting each stitch row by row, gathering the required number of stones and placing them in a corresponding grid-like pattern. The long and painstaking process often brought to mind the process of needlework and was so inherently performative that I filmed several hours of this installation process.

Sylvia Griffin: Hand in Hand installation progress shot (folded pillowcase at lower right), 2013

On many occasions during this installation, parallels to the embodied experience of needlework emerged. At times contemplative, at other times challenging, the physicality of the process – loss of feeling in the fingertips lasting several days, the challenge of kneeling for hours at a time hunched over the work, and lapses in concentration leading to errors in the “reading” of pattern – paralleled, I imagined, those experienced by the needleworkers of the original pieces. I often found myself needing to relinquish my sense of control as the need for compromises arose, such as the running out of a correct stone size, necessitating adjusting the “reading” of the textile and thus my expectations. This too was consistent with the original textile’s history: my close observation of what initially appeared to be near-perfect symmetry in the embroidery revealed several imperfections, which assisted my reconciliation with those in my own piece. Whether the deviations discovered in the original textile were simply mistakes or shortcuts taken by the embroiderer for the sake of speed or another reason, I can never be certain.

Temporal signs such as the deterioration and heavy staining of the original fabric disappeared in this new incarnation, revealing only the marks on the damask support. The title of the work, Hand in Hand, intimates female labour and embodied experience in the work process, as well as contiguity of past and present. The ritualistic handling of each stone recalls and connects handwork, domestic and mourning rituals. The concentration and time necessitated in realising Hand in Hand, as perhaps with dowry embroidery, is a simultaneously contemplative and cathartic experience allowing me to share a story in a similar manner to that shared by my mother’s dowry linen.

Sylvia Griffin: Hand in Hand, installation view, 2013

In reinterpreting the form and function of the original dowry textile as a work of art several other major differences can be observed. Firstly, the scale and materials used challenge the delicacy of the embroidered cotton, translating it into a weighty, grounded object. This itself carries a contradiction with the realisation that each stone sits unattached on the base, vulnerable and unstable. Furthermore, if the stitches of embroidery are considered as a form of the miniature, as I perceive they are, then Hirsch’s linking of miniaturization to confinement and power should also be noted. Hirsch cites Susan Stewart in her book On Longing for her view that the miniature is a “metaphor for the interior space and time of the bourgeois subject” while the gigantic is a metaphor for “the abstract authority of the state and the collective, public life[45].” Hand in Hand presents a challenge to this proposition by bringing the personal and the feminine into the public arena whilst maintaining an intimate connection to the delicate original.

As an artist, I have considered the social, anthropological and historical aspects of dowry linen in an attempt to contextualise the role that a household ritual can play in diasporic homemaking. This research has not only informed and assisted my understanding of my own personal family history, but has also deepened my understanding of the broader implications of dowry, homemaking and a particularly female tradition. The combination of all these factors has enriched my artistic practice, assisting me in expressing the embodied processes inherent in needlework and the rituals of homemaking in an artistic mode. In referencing a familiar custom in physically and materially disparate means via a contemporary artistic practice, the viewer is invited to reflect on the nature of ritualistic processes. My practice aims to reflect and respond to the interconnected aspects of these rituals and offer a fresh means of engaging emotionally.

[1] Effstratia Antoniou Katahan, “Stories of an Immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles” (University of Alberta (Canada), 1997). 1.

[2] Caruth Cathy, Trauma: Explorations in Memory (Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1995).

[3] Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002); The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust (2012); “Past Lives: Postmemories in Exile,” Poetics Today 17, no. 4 (1996).

[4] Brett Ashley Kaplan, Unwanted Beauty: Aesthetic Pleasure in Holocaust Representation (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2007).

[5] Anne Whitehead, Memory, ed. John Drakakis, The New Critical Idiom (London: Routledge, 2010).

[6] ‘Postmemory’ is the term coined by theorist Marianne Hirsch and now integrated into trauma discourse to describe the effects of a second generation’s experience of their parents’ trauma.

[7] Susan Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). 14.

[8] Ibid. 6.

[9] Ibid. 13-14.

[10] Katahan, “Stories of an Immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles.”

[11] Ibid. 1.

[12] Ibid. 57.

[13] Ibid. 57.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Frye uses the term “women’s textualites” to encompass writing, painting and embroidery in this period 1540-1700.

[16] Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England. xv.

[17] Annette Weiner and Jane Schneider, Cloth and Human Experience (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1989). 1.

[18] Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England. 9, 11.

[19]Ibid. 29.

[20] My step-mother, Eva Laszlo, is the same age and from the same Hungarian social class as my mother.

[21] According to my step-mother, her mother and aunt selected a pink cotton for her dowry linen which was ordered from Switzerland. The seamstress who completed the items was a friend (or distant relative) of the family.

[22] Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England. 15-23.

[23] Maurice Mauris, “About Monograms,” The Art Journal (1875-1887) 4, no. New Series (1878). 40-42.

[24] Katahan, “Stories of an Immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles.” 5.

[25] Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 240.

[26] The term ‘transnational home/s’ is used in this paper to denote the migration and resettlement across national borders of migrants – particularly the dispossessed and displaced as described by Blunt & Dowling in their book “Home” (see footnote 35).

[27] Paul Connerton, How Societies Remember (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). 4.

[28] Ibid. 5.

[29] Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 204-207.

[30] Katahan cites this case via L. Welters 1988.

[31] Katahan, “Stories of an Immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles.” 59.

[32] With the symbolon, a symbolic object was broken in half on the drawing up of a legal contract. Each party was given one half and on bringing the two halves together again at a later date, the contract could be ratified.

[33] Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 211-212.

[34] Ilaria Vanni, “Oggetti Spaesati, Unhomely Belongings: Objects, Migrations and Cultural Apocolypses,” Cultural Studies Review 19, no. 2 (2013). 150-151.

[35] Ibid. 153-154.

[36] Alison Blunt, and Robyn Dowling., Home (London: Routledge, 2006).

[37] Ibid. 212-3, 248.

[38] Ibid. 199-205.

[39] Katahan, “Stories of an Immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles.” ii-iii.

[40] Ibid. 33.

[41] Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 186.

[42] The index is one of the triumvirate of signs, alongside the icon and the symbol, developed by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. While the icon resembles or imitates its object (for example, a portrait or diagram), and the symbol has an independent connection to its denoted object (such as words, names or mnemonics), the index maintains an existential relationship to its object, a ‘having-been-thereness’ of that which is signified (such as the smoke of a fire).

[43] Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 215.

[44] Janet Wolff, The Aesthetics of Uncertainty, Columbia Themes in Philosophy, Social Criticism, and the Arts (New York: Columbia University Press, 2088), 60-61.

[45] Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 195.

Bibliography

Blunt, Alison, and Robyn Dowling. Home. London: Routledge, 2006.

Cathy, Caruth. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1995.

Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Frye, Susan. Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

———. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. 2012.

———. “Past Lives: Postmemories in Exile.” Poetics Today 17, no. 4 (1996): 659-86.

Kaplan, Brett Ashley. Unwanted Beauty: Aesthetic Pleasure in Holocaust Representation. Urbana: University of Illinois, 2007.

Katahan, Effstratia Antoniou. “Stories of an Immigrant Greek Woman: My Mother’s Dowry Textiles.” University of Alberta (Canada), 1997.

Mauris, Maurice. “About Monograms.” The Art Journal (1875-1887) 4, no. New Series (1878): 36-42.

Vanni, Ilaria. “Oggetti Spaesati, Unhomely Belongings: Objects, Migrations and Cultural Apocolypses.” Cultural Studies Review 19, no. 2 (September 2013 2013): 150-74.

Weiner, Annette, and Jane Schneider. Cloth and Human Experience. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1989.

Whitehead, Anne. Memory. The New Critical Idiom. edited by John Drakakis London: Routledge, 2010.

Wolff, Janet. The Aesthetics of Uncertainty. Columbia Themes in Philosophy, Social Criticism, and the Arts. New York: Columbia University Press, 2088.